High-school Social Studies teacher Steven Serling knows what democratic engagement can do for young people. A advocate of learning-by-doing, Mr. Serling emphasizes the way in which youth participation in PB encourages young people to become engaged citizens, effective communicators, and thoughtful decision makers.

Unsurprisingly, Mr. Serling has been nominated for a hometown hero award. He’s certainly got our vote!

How old are your students, and what kinds of classes are PB-goers enrolled in?

I teach 12th grade students at Park East High School in East Harlem, Manhattan. Most of my students are anywhere between 16 and 18, and I teach social studies—so economics and government classes. While my entire class doesn’t participate in PB, I kind of throw the option out there and interested parties attend.

What got you interested in PB? What made you want to get your students involved?

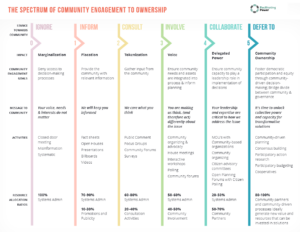

I’ve always liked to get students outside of the classroom, and a lot of what I do and what I’m interested in is getting students to truly experience their community. My goal is that they enjoy their community, they utilize their community, and they feel like a part of their community. To do that, my assistant principal, Dr. Suzy Ort and I felt that one of the activities that was very practical—and aligned with my curriculum surrounding participatory government—was student involvement in PB. It’s truly a way for youth to be directly involved in democracy.

I’d imagine that the first challenge is getting them into it: what really got your students interested? Are there hot-button issues for them?

Well, in Economics we talk about the allocation of scarce resources, and in my Government class we also talk about how we can improve and engage our communities with resources. So, when we started talking about the needs and wants of our community, what seemed to be most important to my students were issues within the school—specifically surrounding technology.

Right now we have three full laptop carts and smartboards that we actually got through a previous PB cycle. So, the kids know that PB is a viable way to improve our school—that it truly affects them and is very real. And that’s the difference. When I talk about government in a theoretical way or about current events in the classroom, they’re learning about it, but it’s not the same. With Council-Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito’s office spearheading PB here in District 8, the students really get a feel for democracy and the workings of our government.

What was working with her office like?

She’s certainly one of the huge supporters of PB here in New York City. She allocated $2 million to District 8’s process this year and lowered the PB voting age to 14. So now all our High School students—from grades nine through twelve—can be part of the process. So she’s really gone above and beyond. Her Director of Community Affairs, Max Cantarero spearheaded the day-to-day process working with my students, helping them understand the entire process from the beginning. It’s not everyday that youth get to work together directly with government officials.

Educators and the public are often interested in creating a conversational, engaged, and cooperative classroom dynamic. Did having some students go to PB meetings affect classroom discussion at all?

In terms of learning, I think it went beyond becoming familiar with resource allocation and government voting for my students. These kids got to meet other people who care deeply and are engaged in their community, they learned how to work in groups with strangers, and they developed skills to reach a consensus though engaged, constructive discussion.

What surprised you or the students about the process? What were the challenges?

The surprise for my students was that they could actually be involved in government. You tend to assume that older people—only those who are elected officials—have a real say in what does or doesn’t happen. But the students felt like they were part of something real and effective.

One major challenge was actually winning our project. This year we lost, so there was some disappointment, but it’s definitely a learning experience all around, and the five projects that were chosen seem like they’ll improve our community too.

And we’re already thinking about possibilities for next year’s projects! I know that one idea that was floated around already was the prospect of creating a green roof for our school. We have an unused roof on top of the building with an emergency lock on it, and it’s really a large space. Kid’s were saying, “What if we could go out there for lunch? Couldn’t science classes use it? What if we had composting out there?” A bunch of ideas were being generated.

Do you anticipate making any changes in the way you get students involved in the process or in the way you shape curriculum around PB?

Yes, I actually think I’m going to teach a complete unit on PB now. It’s such a tangible, important governmental process. The actual class that I teach is called “Participation in Government,” and PB could be an integral part of that particular class.

Is there anything else that you’d like to say?

Schools, public housing and many other institutions that use PB have many needs and wants that are often unable to be funded through their normal budget allocations. PB makes public funds available that directly help community institutions attain some of their needs and wants to benefit so many people.

I’d also like to emphasize that the youth component of this process is very unique. The fact that PB let’s young people get involved in government is not really the norm. The PB process gives them ownership in their city. That kind of ownership will hopefully help them become well informed, positive, and involved citizens of their communities later in life, and that’s why I think PB is very powerful, and should be modeled across the nation.