In this guest post, Pratt Institute‘s Laura Stinger recaps a panel discussion held in Brooklyn on October 29th, to discuss Chicago’s recent experience with participatory budgeting, and the possibilities for similar initiatives in New York:

During an evening event held at Pratt Institute to discuss the future of participatory budgeting in New York City, Chicago Alderman Joe Moore was joined by New York City Council Member Brad Lander, Bronx Community Board 7 District Manager Fernando Tirado, and Community Voices Heard representative Anne Washington. This post recaps the presentations and discussions from the event.

After introductions by Eve Baron of the Pratt Center, the Alderman screened a short film to illustrate the participatory budgeting (PB) process in his ward, from formation of the steering committee, to brainstorming sessions, to presenting ideas, and finally voting. After the film, the Alderman explained why he felt compelled to use participatory budgeting as a way to tackle the lack of citizen influence in city government.

In Chicago, most city-wide decisions are made by the mayor, while ward decisions are left to each Alderman. In spite of the Aldermen’s significant influence on local zoning, capital expenses used to be concentrated in the downtown area. In the mid 1990’s, as a way to spread money out more evenly, Aldermen were given “menu funds” to spend on infrastructure improvements as they saw fit.

After hearing about participatory budgeting at the US Social Forum, Alderman Moore decided to explore the feasibility of using PB to distribute his menu funds. He liked the idea that it would involve his constituents in a process that was infamous for its lack of transparency. While a lot of politicians balk at the idea of giving up any power, Moore found that in giving up power to the people, he also gained power. After roughly 20 years in office, he feels that participatory budgeting has been his most popular initiative.

Moore’s jurisdiction, Chicago’s 49th Ward, lies in Rogers Park, a racially and economically diverse community of over 60,000 people. After forming a steering committee of community leaders to design the process, the Alderman’s office held nine neighborhood assemblies, including one for Spanish speakers. The Alderman explained the PB process and then participants broke into groups to discuss potential spending projects.

People were invited to stay involved as “community representatives.” These representatives then met for several months in six committees, to gather more ideas from the community and develop specific proposals to put on the final ballot. In April, all residents of the ward (even those who were not citizens, documented, or registered to vote) were invited to vote on the spending proposals. 1,600 people showed up to vote. After the results came in, the Alderman’s office began implementation.

Moore explained that the process is evolutionary, and is still being tweaked and improved. For instance, even though streets need to be resurfaced, the street improvement proposals did not receive many votes. The way streets projects were proposed (block by block) made people less likely to vote for projects that were not on their block. This year, the ballot will also ask voters what percent of the budget should go to street resurfacing, so people begin to think more globally.

According to Moore, the whole initiative cost $7,000 and required one staff member. Most costs went to printing and advertising. Moore acknowledged that it was very time consuming, but also that the rewards included good government and more political clout.

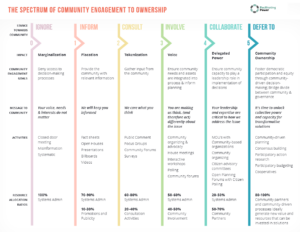

The conversation then moved to the possibility of using PB in New York. Brad Lander compared the NYC budget and planning process to Chicago’s. Discretionary funding, the money allotted by the speaker to each council member, is a small part of the NYC budget. Each council member has a capital pot and an operating expense pot, and the amounts given to each council member differ. Community boards also have a process where they compile budget priorities, often asking council members to spend their discretionary dollars in certain ways or asking the city to budget certain ways. The budget priorities established by the community boards are not attached to a guarantee of city funding, however.

One challenge of distributing the capital discretionary funds is that the money is used for parks upkeep and technology upgrades in schools, because the mayor’s office has pushed those responsibilities to council members. Once Lander funds those important services, he doesn’t have much money left. As to his operating expense funds, Lander gave out grants in small chunks to non-profits in his district. He suggested that community boards and council members could work together in a PB process. A barrier, however, is that the geographic boundaries of the two bodies are different. Lander also asked if PB could affect NYC budgets as a whole, beyond discretionary funds.

Fernando Tirado spoke next, from the perspective of community boards. Community boards submit capital and expense requests to the city, but they usually hear in response, “Take these requests to your elected official. There’s no money from the city for them.” Budgetary recommendations are made over and over for 10 years sometimes and often don’t get funded. For Tirado, community boards are less effective because they only have an advisory role. Not only is the city not required to fund the boards’ capital and expense recommendations, but the CB’s do not even have enough money in their operating budgets to be effective.

Tirado agreed with Lander that there is a need for community boards to have consistent, co-terminal boundaries with city council districts. While CB’s don’t have the power to do participatory budgeting, they already have committees in areas very similar to the committees in the Alderman’s PB process: parks, transportation, the arts, safety, etc.

Anne Washington, a representative of the organization Community Voices Heard, expressed frustration with the lack of respect for community member opinions in planning and development decisions. According to Washington, people in her community feel that government does what it is going to do without community input. She argued that elected officials must be in the community listening to people. The real cause of a perceived lack of citizen interest in local decision making is that they feel that their desires aren’t taken into consideration when the shovel hits the pavement. People don’t vote, she said, because they feel their voices aren’t heard.

Washington suggested that PB should happen at the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA). As she explained, problems abound, and the people living in NYCHA are the most qualified to direct funds to fix them. The money is there but residents have no control over it, and the existing tenant representative system isn’t effective.

By the end of the talk it was clear that, while all the speakers supported PB, there are significant hurdles to making PB a possibility in New York City. The discretionary funds available to council members are being eaten up filling gaps left by a dwindling city budget. The community boards are structurally ready to support a PB process, but they have no real power over the city budget, and their operations budgets are stretched beyond capacity as it is. Because the community boards are often perceived as ineffective and not adequately representative of the communities they serve, citizen participation is low.

Nevertheless, Alderman Moore’s PB initiative remained inspiring. The essence of PB, and what makes it so progressive, is that it gives community members direct access to resources by removing the distance and opacity that currently lies between citizens and government decision making. Alderman Joe Moore used creativity to make PB happen in his ward. In the end, his ability to find out-of-the-box solutions were what fulfilled the promise of PB, changed the dynamic of local government, and gave citizens a direct way to interact with democracy.

To watch videos of the Pratt Institute event, click here.

Could Participatory Budgeting Work in New York?

- November 23, 2010

- Blog

Post Tags :

Participatory Budgeting Project

PBP helps communities decide how to improve using public money.